Can Goats Eat Walnut Leaves? Essential Guide

Yes, goats can technically eat walnut leaves, but it requires extreme caution because walnut wood and leaves contain juglone, a compound that can be toxic, especially to horses and some other animals. For goats, moderate, occasional exposure is usually tolerated, but large amounts or fresh cuttings should be avoided to prevent potential digestive upset or toxicity issues. Always monitor your herd closely.

Welcome to the workshop! As someone who loves working with wood—from building sturdy tables to crafting useful shelves—I know how important it is to understand the materials we handle daily. Sometimes, those materials cross over with our other hobbies, like raising livestock. If you’ve recently pruned your black walnut tree and wondered if those branches or leaves are safe for your goats to munch on, you’re asking exactly the right safety question. It’s frustrating when usable yard waste creates a big question mark about animal safety. Don’t worry, we’ll clear up the confusion surrounding walnut leaves and your friendly herd. Let’s dive into what makes walnut unique and how to keep your goats healthy while managing your property.

As a woodworker, I handle walnut lumber all the time—it’s dense, beautiful, and strong. But when we move from the workshop to the pasture, the rules change entirely. Trees that make fantastic furniture can sometimes pose risks to our livestock. This is especially true when dealing with the walnut tree (Juglans nigra), which produces a natural substance that can cause trouble depending on the animal.

So, can goats safely snack on those fallen walnut leaves or branches you’ve cleared out? The short answer is complicated, leaning toward “be very cautious.” We need to talk about a compound called juglone. Let’s break down the science in a simple way so you can manage your land and keep your goat herd happy and safe.

Understanding the Walnut Toxicity: The Role of Juglone

The main concern regarding any part of the walnut tree—the leaves, the hulls around the nuts, and even the roots—is a naturally occurring chemical called juglone. Juglone is a natural defense mechanism for the tree, preventing many other plants from growing too close (a phenomenon called allelopathy). For livestock, juglone can be a serious issue.

What Exactly is Juglone?

Juglone is a naphthoquinone. Think of it as a natural inhibitor or poison that the tree produces. While it harms many insects and plants, its effect on animals varies widely. For instance, horses are extremely sensitive to walnut, often developing laminitis (a painful hoof condition) just by standing on fresh wood shavings from walnut bedding. Goats, thankfully, show higher tolerance, but that doesn’t mean they are completely immune.

Which Parts of the Walnut Tree Contain Juglone?

It’s crucial to know where the danger lies. Juglone is present throughout the tree, but its concentration shifts:

- Walnut Hulls (Green Outer Covering): These usually have the highest concentration of juglone, especially when fresh.

- Leaves (Especially Fresh/Green): Moderate to high levels of juglone. When leaves dry out, the concentration often decreases, but they remain risky when freshly fallen or green.

- Bark and Roots: Juglone is present, making proximity or root contact a concern.

- Dried Wood/Sawdust: While lower than fresh leaves, using fresh walnut sawdust as bedding for any livestock is strongly discouraged (especially horses).

Goats and Juglone: Tolerance vs. Danger

When we look at goats (Capra aegagrus hircus), we generally find they are more resistant to toxins than animals like horses or ruminants with very sensitive digestive systems. This doesn’t give us a free pass, however.

Why Goats Might Tolerate It Better

Goats are famous browsers, meaning they eat a very wide variety of plants—many that other livestock (like cattle) refuse. This diverse diet often means their digestive systems are more robust and adapted to handle somewhat questionable forage. Furthermore, studies on goat toxicity largely focus on the hulls or extreme exposure, finding that goats generally do not develop the severe hoof issues seen in horses from bedding.

When Does Walnut Become Dangerous for Goats?

The risk increases significantly under certain conditions. We need to be diligent about preventing concentrated doses:

- Large Quantities: If a goat is forced to graze exclusively on or near large piles of fresh walnut debris, the cumulative juglone load can cause serious digestive upset, diarrhea, or, in severe cases, signs of toxicity (lethargy, loss of appetite).

- Fresh, Green Material: Fresh leaves and twigs contain active juglone. As leaves wilt and dry, the compound degrades, reducing the immediate hazard.

- Compromised Health: A goat that is already sick, pregnant, or young/very old might react poorly to even small amounts of potential toxins.

Since we are aiming for high-quality care, the safest approach is to treat walnut leaves as “feed with caution” rather than “safe forage.”

Practical Management: Pruning and Disposal Guidance

If you have a black walnut tree on your property, managing the trimmings is essential. Here is how you can safely handle that pruned material without putting your goats at risk.

Step-by-Step Safe Disposal of Walnut Prunings

This process ensures that any material containing juglone is kept far away from your goats’ reach until it is completely aged or disposed of properly.

- Isolate the Debris Immediately: As soon as branches or leaves are cut, use fencing, tarps, or separate pens to physically block access for all goats, kids, and even pregnant does.

- Allow for Drying (The Waiting Game): If you choose to dry the material, move it to a completely enclosed area or a distant compost pile where goats cannot easily access it. Allow the material to dry thoroughly for several weeks. As the leaves cure and turn brittle brown, the juglone concentration lowers significantly.

- Monitor for Accessibility: Regularly check the drying pile. Goats are clever! Ensure winds haven’t blown fresh leaves back toward the pasture line.

- Consider Composting Risks: While composting can break down the toxins, improper, hot composting might not eliminate all juglone quickly. If you compost walnut material, keep it separated from your general bedding/feed compost for at least six months. Consult resources on allelopathic composting like those from university extension services, such as Penn State Extension, for best practices on managing wood waste safely in compost systems.

- Disposal Alternatives: If you are unsure or have a large volume, the safest route is removal. Burn the debris (where permitted and safe) or chip it and use the chips on non-pasture areas or pathways far from your animals.

Creating Safe Browse Zones Near Walnut Trees

Sometimes, goats naturally gravitate toward trees they shouldn’t eat. You can protect your walnuts while still allowing beneficial browsing:

- Physical Barriers: The easiest method is wrapping the trunk of the walnut tree with chicken wire or hardware cloth up to about 6-8 feet high. This prevents them from eating the bark or lower branches.

- Fencing Off the Drip Line: If the tree sheds a lot of leaves over a specific area, install temporary netting or electric fencing around the drip line during high-shedding seasons (fall) or right after pruning.

- Provide Superior Alternatives: Goats browse because they like to browse. Ensure they have access to plenty of safe browse species (like willow, mulberry, or thistle) mixed into their diet to reduce their temptation to sample risky items like walnut leaves when they are available.

Comparing Walnut Leaves to Other Common Goats Forages

To give you confidence in what you can feed, here is a quick comparison to put walnut in perspective. Remember, variety is the cornerstone of intelligent grazing.

| Plant Name | Juglone Present? | General Safety for Goats (Moderate Intake) | Notes for Homesteaders |

|---|---|---|---|

| Black Walnut Leaves (Fresh) | Yes (Moderate) | Use Extreme Caution / Avoidance Recommended | Risk of digestive upset due to juglone concentration. |

| Black Walnut Leaves (Dried/Aged) | Low | Low Risk, but monitor intake | Safer once fully cured, but never a primary feed source. |

| Mulberry Leaves | No | Excellent / Highly Recommended | A favorite browse; safe and nutritious. |

| Maple Leaves (Sugar/Red) | No (Red Maple is Toxic) | Safe (Except Red Maple) | Ensure you are not mistaking walnut debris for maple debris; Red Maple is highly lethal to ruminants. |

| Oak Leaves (Mature) | No (Tannins Present) | Moderate Risk (Tannins) | High tannin content in large quantities can impact digestion, though usually tolerated better than walnut. |

This table helps emphasize that while many plants have minor risks (like tannins in oak), juglone in walnut is a specific chemical hazard that requires stricter management.

Recognizing Signs of Potential Walnut Toxicity in Goats

Even with the best preventative measures, it is crucial to know what to look for if you suspect your goats have ingested too many walnut leaves or hulls. Early detection is key to successful management.

Subtle Signs to Watch For

Toxicity symptoms in goats from plant ingestion are often general signs of distress. Be alert for:

- Sudden decrease in appetite or complete refusal to eat their usual hay or grain ration.

- Listlessness or excessive lethargy; standing apart from the herd.

- Unusual droppings (scours, severe diarrhea, or change in consistency).

- Excessive drooling or frothing around the mouth (less common with juglone than with certain other toxins, but possible).

- Weight loss over a short period if consumption has been ongoing.

Immediate Action Steps

If you confirm or strongly suspect your goats have accessed fresh walnut debris and you notice any of the above symptoms, take these immediate steps:

- Remove All Access: Immediately stop any potential source of the leaves, hulls, or contaminated hay/feed.

- Offer Fresh Water and Hay: Encourage gut motility by providing plenty of clean water and palatable, safe forage like timothy hay. Sometimes, flushing the system helps dilute the toxin.

- Contact Your Veterinarian: Because juglone toxicity can affect internal organs, professional guidance is vital. Describe exactly what you think they ate, how much, and when. They may recommend supportive care or specific interventions.

Remember, prevention is always easier than cure in livestock management. Think of it like handling hazardous materials in the workshop—you wouldn’t use treated wood indoors without proper ventilation; likewise, you shouldn’t feed potentially toxic browse without checking the safety data first.

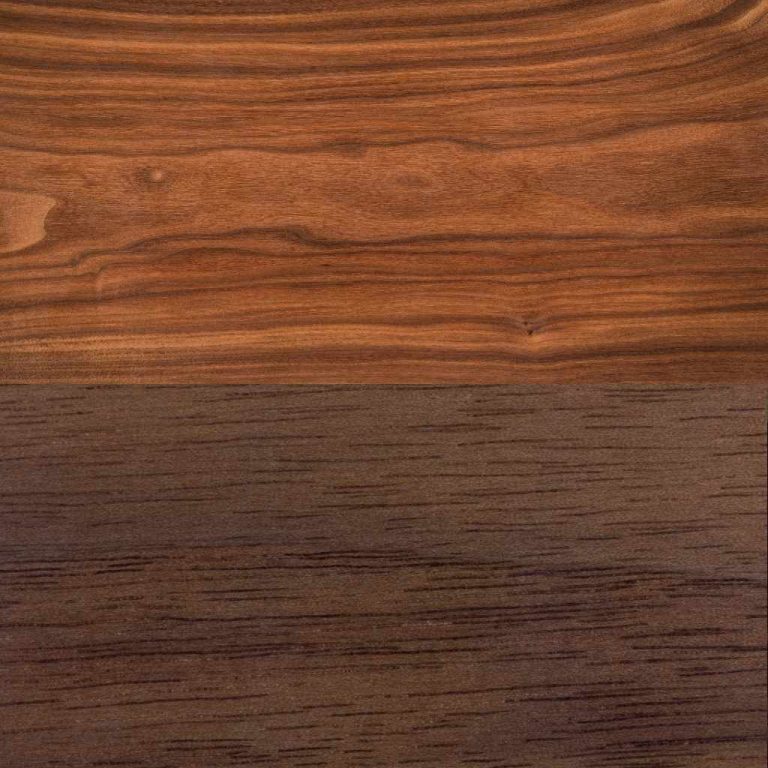

Why Walnut is Great for Woodworking, But Not Goat Feed

As a woodworker, I can wax poetic about black walnut. It’s one of the premier domestic hardwoods in North America. It finishes beautifully, machines wonderfully, and commands a premium price for good reason. This dual nature—valuable timber versus potential poisoning agent—is fascinating.

When you look at a freshly milled black walnut slab, you see rich color and incredible potential. When you look at the leaves falling in the pasture, you must see potential danger. This disconnect is important for homesteaders who manage both land use and livestock.

For example, when building a strong, durable garden bed or raised planter for your vegetables, walnut wood is often recommended due to its natural rot resistance (as cited by many construction and landscaping guides). However, the chemical that makes the wood durable internally is the same one we worry about in the leaves: juglone.

Safety Tip for Woodworkers with Goats: If you are milling walnut lumber, ensure ALL sawdust and scraps are stored in a secure, covered location far from where your goats graze or browse. Never use walnut shavings for livestock bedding.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ) About Goats and Walnut Leaves

Q1: Are dried walnut leaves poisonous to goats?

Dried or cured walnut leaves significantly reduce their juglone content compared to fresh ones. While they are much safer, they should still not form a significant part of the goat’s diet. Excessive consumption of any dried plant material can cause digestive issues.

Q2: How long does it take for walnut leaves to become safe after falling?

There isn’t a fixed scientific timeline, but the toxin degrades over time, especially with exposure to sun and air. Most experts suggest allowing leaves to dry and weather for several weeks, ensuring they are brittle and brown, before allowing any grazing nearby.

Q3: Will goats eat walnut leaves if other forage is available?

Goats are curious browsers. If clean, tasty forage is plentiful, they will usually ignore the walnut debris. However, in sparse pastures or during limited feeding times, they are far more likely to sample the leaves. Keep pastures well-managed to prevent this temptation.

Q4: Is walnut hay safe for goats?

No, feeding walnut hay is highly discouraged. Even if the hay appears mostly dry, preserved bales can retain enough active juglone to cause harm, especially since hay is eaten in large volumes. Stick to proven safe hays like grass or alfalfa.

Q5: Can goats get the same hoof problems as horses from walnut?

It is highly unlikely. The severe laminitis associated with walnut exposure is overwhelmingly documented in horses. While goats can suffer systemic poisoning, the specific hoof reaction seen in equines is not typically reported in goats.

Q6: What about the green balls (walnut hulls) on the ground?

The green hulls surrounding mature walnuts contain very high levels of juglone. Keep goats completely away from areas with fallen green hulls. They are much more dangerous than the leaves alone.

Q7: Can I let my goats browse the tree canopy in the fall?

If your pasture backs up to a walnut tree, monitor heavily in the fall. A few stray leaves might be fine, but if they can reach and strip branches, or if the ground beneath is covered in fresh fall leaves, you must fence them out until the leaves have fully decomposed or blown away.

Building Confidence in Your Homestead Forage Decisions

Managing livestock safely, especially when your trees and pasture meet, requires continuous learning. Just like in woodworking, where we learn the specific properties of pine versus oak, we must learn the specific risks associated with every plant on our property.

We confirmed that while goats show more tolerance to juglone than some other animals, treating fresh walnut leaves and debris as a known potential hazard is the most responsible approach. Your goal as a caretaker is to eliminate risk, not test tolerance thresholds.

By being proactive—isolating fresh cuttings, creating physical barriers, and monitoring your herd closely—you ensure your goats remain healthy while you manage your trees. You have the skills to build and maintain—apply that same diligence to managing their environment. A safe goat is a happy goat, and a healthy herd allows you to focus on your next woodworking project, worry-free.