Disproven: Do Bees Like Cedar Wood Secrets

Bolded Quick Summary (Top of Article)

Despite common rumors, busy honeybees and beneficial native bees generally do not have an increased attraction or preference for untreated cedar wood specifically for building colonies or nests. Cedar poses maintenance challenges. We will explore why this myth exists and what wood is actually best for hive building.

Why Are We Talking About Bee Nesting in Wood?

Wood is essential for keeping our busy pollinators happy and safe. Many of us know that honeybees build wax combs inside sheltered spots, often mimicking hollow tree trunks. Because cedar shelves and outdoor projects resist rot so well, many DIY beekeepers wonder if insects like cedar for their nests. If you are setting up your very first beehive, chances are you are asking, “Do bees like cedar wood?” or “Will building my hive box out of cedar repel stinging pests?

It is easy to get different, confusing advice circulating on hobby forums. Worry not! I am here to clear this up so you can make smart, durable choices for your new investment. We will look at science basics, the pros and cons of cedar for beekeeping, and what materials experienced mentors actually recommend building with for longevity and safety. You absolutely can build a successful hive or bug house with confidence.

The Eternal Backyard Question: Myth vs. Reality for Cedar and Bees

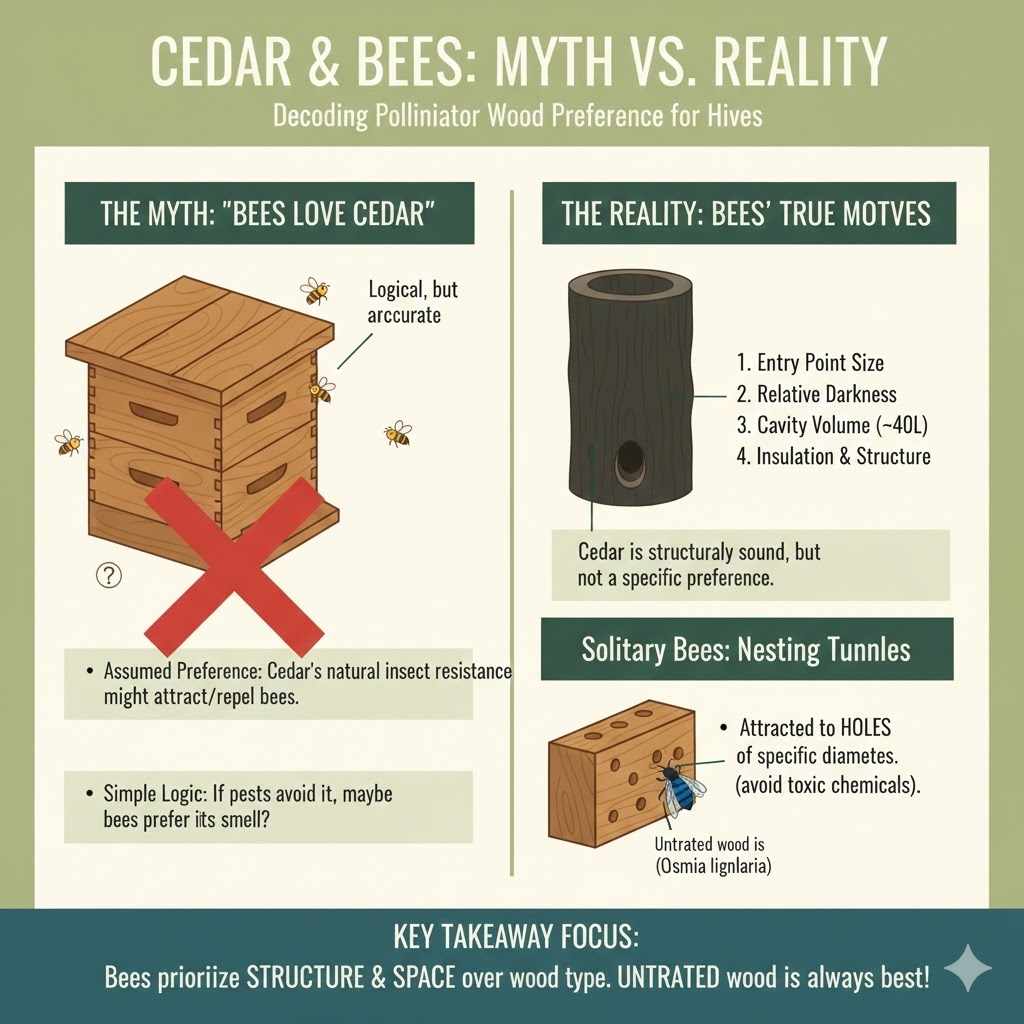

The specific myth that suggests “bees strongly prefer cedar for hive construction” crops up a lot. It seems logical: cedar is a famous exterior wood used for decks and fences because it is naturally resistant to both decay and insects like termites according to resources like the U.S. Forest Products Laboratory on wood durability ratings. If general pests avoid cedar, surely bees should avoid it too, or maybe even prefer its smell for some mysterious reason?

The reality, however, is much simpler once you understand bee behavior. Bees choose nesting spots based on four main tenants: entry point size, relative darkness, existing cavity size (about 40 liters is ideal for good honey production), and insulation/structural integrity. Many cedar planks seem perfect structurally. But specific wood chemistry doesn’t override the basic need for a safe, weather-tight fortress.

Your instinct to research is the number-one mark of crafting true quality. Let’s break down what properties of cedar actually matter versus what the traditional beliefs suggest.

Understanding Wood Preference by Pollinators

When we consider pollinators, we need to separate honeybees (who live in large vertical colonies) from our thousands of species of solitary and native bees (like mason bees or leafcutter bees) who nest in narrow tunnels or pre-existing holes.

How Honeybees Choose a Home

For honey production colonies, they simply need insulation and space within a predator-proof shell. They will take almost any structurally sound box if the entry and inside volume checks out. Cedar ticks the ‘sound structure’ box, often better than materials like pine (depending on pine preservation).

Mason Bees and Resin Coating

For solitary pollinators, like the Blue Orchard Bee ($textit{Osmia lignaria}$), they look exclusively for holes of specific diameters to lay their larvae—things like drilled blocks, cardboard tubes, or reeds. They are simply attracted to a drill-entry, not usually the wood type itself—unless that wood is covered in potentially toxic chemicals. Untreated wood is the key here for almost all desirable insects.

Key Takeaway Focus: While honeybees are not “averse” to well-built cedar boxes, no compelling evidence suggests they are actively choosing cedar over other comparable, less expensive woods like common pine.

Dispelling The Common Misconception: Why People Think Bees Love or Hate Cedar

If bees don’t seem bothered by high-quality cedar nesting boxes, where did this confusion originate? It usually lies in observing general differences between cedar’s properties and traditional honeybee hive manufacturing standards.

Point 1: Cedar Odor Release

Cedar’s great selling point—that light, comforting aroma—is what often throws beginners. That pleasant smell is an organic oil (ketones in cedar are what provide the odor noted by entomologists). Some garden hobbyists mistakenly concluded that this pervasive scent could attract insects seeking wood resources for consumption (like bark beetles, which cedar deters), or, conversely, assume the scent is off-putting, thus concluding nobody likes cedar. Neither is precisely what bees want! Bees track food sources and humidity, not wood cologne.

Point 2: The Cost Factor vs. Value Judgment

Good solid Cedar (like Western Red Cedar) is significantly pricier than untreated Pine or Canadian Hemlock. If a beekeeper buys an entire expensive cedar-only setup, that owner is inherently paying premium for maintenance, not proven superior functionality. Early beekeeping books recommended pine simply because it was cheap, readily available material used for constructing many common DIY structures. The workability often drives beginner wood recommendations more than bee preference.

Exploring the Real Pros and Cons of Using Cedar for Bee Hives (The Beeproof Analysis)

As a woodworker and someone highly invested in durable outdoor DIY, I understand cedar’s appeal. It resists rot better than many softer alternatives because specialized organic extractives naturally ward off moisture damage. For a high-wear item like a hive body subjected to seasons of sunlight and rain, robust wood matters!

Here is an objective structure for beginner clarity:

Table 1: Comparison of Cedar vs. Pine for Beekeeping Boxes (Untreated)

| Property | Western Red Cedar (Recommended) | Untreated Pine/Fir (Common Standard) |

|---|---|---|

| Rot Resistance | Excellent | Poor to Fair (Without chemical preservative) |

| Weight (Easier Lifting/Moving) | Medium-Light | Medium-Heavy |

| Cost Factor (Approx.) | High | Low-Medium Draft Workability, Very easy to cut/drill/etc. |

| Insulation Value | Good density yields good thermal mass | Fair |

| Bee Nest Approval Rating | Unnecessary Preference Evidence: Neutral Score for Either | |

Relative cost compared to lumberyard baseline prices.

The main attraction of cedar is its longevity. If you want a hive body that you expect to get 15–20 years out of with minimal water-logging damage (assuming excellent ventilation inside the hive), then premium wood offers physical durability. But bees will adapt well to Pine providing you never treat it with stains, sealants, or lead-based paint—old standards sometimes used carelessly 50 years ago that truly do repel bees (or harm larvae).

If we talk about predator evasion, while rot-resistant wood is fantastic support material, bees dislike high heat or extreme movement. These are the threats cedar doesn’t truly mitigate better than thick pine insulation. A thin piece of cedar breathes differently than the thick stack of pine an original hive might occupy naturally. This brings us to crucial measurements regarding hive health, focusing on insulation.

- Thickness Equals Insulation: Bees MUST successfully winter colonies by clustering tightly inside the cavity (maintaining 95°F internally regardless of outside temperatures). Thicker walls offer better defense naturally than thin, even if that wood is dense cedar.

- Ventilation is Gold: Bees can tolerate lots of external environmental factors—cold, heat spikes included. But they must expel excess moisture from condensed breath. Great ventilation management (found often with telescoping tops!) solves almost all weather challenges, far outweighing debates between board brands being Pine or Cedar.

- Predator Risk Analysis Bees do care far more about the entrance reducing airflow for robbing wasps or keeping hungry woodpeckers out than what type of wood flavor you cooked up for the frame shoulders. Proper placement matters tremendously.

When Cedar Can Become the Problem, Not the Solution

For the beginner beekeeper, the risk involves finishing the cedar unnecessarily. Because cedar smells great naked, new DIYers often feel the urge to “protect its beauty” exteriorally with standard staining or external weather treatments when building the hive supers and floors.

Cedar resin or the solvents/carriers in many typical exterior sealants used outside or inside are toxic or simply offensive. In beekeeping education (check instructional materials used across agricultural extension offices), only approved, food-safe exterior treatments (if required at all) for standard pine/fir boxes are officially supported.

NEVER apply linseed oil, wood preservative chemicals, or heavy UV-blocking paints near bee contact areas (always leave the outside bare or use very light, beeswax/natural mineral oil finishes externally only).

To gain greater confidence without the price tag of top-tier lumber, good carpentry and sealing joints correctly solves 90% of weatherproofing issues; cedar simply provides a little natural backup support, saving your repair time down the roadway. Focus construction time on tight framing rather than hunting for specific odor-free planking.

Beyond the Honeybee: Do Native & Mason Bees Prefer Cedar?

It is fascinating how much attention we sometimes put only on the domestic European Honeybee ($textit{Apis mellifera}$). If you have a general interest card garden or a pollinator pit stop, you are aiming to help native, solitary bees too! Are we accidentally dissuading mason bees from using your beautiful backyard cedar structure while focusing on the honey super at lawn level?

The materials needed for Native and Mason bees look different architecturally from major western hives. Mason/Leafcutter bees want specific, dry tunnel-boring wood with incredibly precise drilled hole locations (diameter consistency is king). Their main danger is mold/rain penetration weakening the tube structure or excessive humidity leading to larvae losses.

The Key Difference in Tunnels

When setting up bee homes for solitary nesters (often called ‘bee hotels’):

| Habitat Feature Desired | Cedar Material Consideration | Best General Practice |

|---|---|---|

| Longevity/Dryness | Excellent. Wood holds integrity well against the elements compared to softer woods, reducing collapse risk. | Mount high, tilted slightly downward toward the draining opening to prevent rain ponding on entrance surface supports. |

| Hollowness/Tunnel Structure | Holes must be cleanly drilled to precise internal diameters. If drilling, follow NIH methodology (or equivalent) for proper sizing/rebating. Look up specifications endorsed by agricultural colleges studying specific $textit{Osmian}$ or $textit{Megachile}$ species populations in your area using $text{Bee Better Niches}$ approach documents for reference data for precise hole diameter vs species profile. | Ensure drilled blocks feature no splintered edges inside the entrance edge opening—use a counter-sink cutter to smooth the opening lip carefully—unsmoothed edges dissuade female builders. |

| Surface Treatments | MUST remain unfinished inside the holes. Any odor from stains, oil residue, or varnish on exterior elements can create fumes harmful or bothersome inside the close housing tube. | Never plug ends of homemade tubes—only sealed structural entrances allowed is paramount. Never put paint brushes inside cleaning access tubes. |

For native pollinators, the specific wood type becomes practically irrelevant (as long they are free of toxins and dry) because all selection pressure focuses on hole size, depth, lack of existing wasp neighbors, accessibility from sun, and dryness within the material structure. In summary: cedar poses practically no benefit and slightly enhances overall material preparation confusion factor for the solo nature houses. Aim for easy stability/dryness, which cedar provides well architecturally.

Setting Beginners On The Most Efficient Path: Tools & Preparation (Safety First!)

If you decide you love the aesthetics and are happy spending a bit more upfront for longevity, here is a quick guide to safely processing cedar for beekeeping or home projects (where no toxins touch the inside cells). Remember, sharp tools are crucial for safe and precise beginner work. If you have never operated power tools unsupervised before, have a guide alongside you. Safety is part of good craftsmanship! Check safety reviews from OSHA resources for portable saw operation best practices if needing review reinforcement on guard usage.

If planning major woodworking, ensure you practice cuts on scrap lumber first. These methods focus only on quick, durable hive construction readiness involving rectangular boxes (Supers).

Basic Assembly Checklist: Creating Durable Boxes from Cedar Planks

- Measure and Mark: Double and triple-verify dimensions against your chosen hive schematic (Langstroth is standard for most beginners: typically an 8-frame hive structure setup for standard sizing).

- Cutting Large Sections ($textit{Caution}$): Use a trusty table saw (or circ saw with a sturdy, straight guide sled setup) to rip planks to the final width needed for wall thickness (standard often utilizes something near 3/4-inch depth lumber, though adjust for your plan).

- Cutting Precise Ends (Squaring): This is NON-NEGOTIABLE! The alignment where boxes/frames connect MUST be 90 degrees if you cut them longwise relative to the width of the frame slot. Nothing collapses confidence faster than corners that waffle in and out one corner slightly crooked. Use a reliable Miter Box when cutting edges if power saws aren’t available, checking every piece with a reliable combination square you purchased from a known tool manufacturer.

- Assembly: Gluing and Clamping: Generous application of waterproof, exterior-grade polyurethane glue (e.g., Type III or IV, frequently available at home center chains labeled weather or exterior sealant appropriate for porch building) is essential. Tight clamps draw corners flush whilst the glue cures strong overnight.

- Fastening: Nailing vs. Screwing: Beginners often struggle here. Screws hold better long-term against the constant structural rocking of full hive weights, but sinking weather-treated nails can look cleaner for first-timers and moves slightly quicker once you master the technique. Do 4 large, spaced nails/screws per long seam for sturdy buildup unless relying solely on screw/girts from top frames.

- Optional Finishing (Exterior): NEVER PAINT OR SEAL INSIDE OR WHERE BOXES STACK UP MOST. Leave exposed wood surfaces like outer lids or insulation lids unfinished if you are using high-quality cedars—Cedar is naturally robust. If using cheaper pine, an exterior paint once only, months prior to colony arrival, that completely covers the wood leaving NO pigment touches raw/edge contacting parts, assists durability without alarming protective chemicals.

This careful build respects the lifespan needed for any lasting outdoor construction, ensuring structural quality. Whatever slight, perceived odor difference Cedar vs. Pine possesses, it is overwhelmed by quality assembly and excellent weather resistance granted by tight, professional-like construction methods that minimize exterior cracks where moisture creeps in!

Understanding the Importance of Wood Type Choice Based on Regional Climate

As your mentor, I must stress that local environment plays a larger role than natural wood pleasantness to a bee. Where are you located? High humidity versus extreme hot/dry winters drastically changes necessary characteristics.

Cedar shines brightly where:

Rainfall and high humidity levels stress wood longevity. (Durability Benefit)

You need lighter moving weight for regular inspection activities typical of annual honey harvest/inspection in southern regions where you manage heavier boxes of sticky summer honeyflow product.

However, thick pine proves very effective where:

Winter freeze/thaw cycling causes issues on standard pine structures. Thicker pine insulation performs very well if you reduce ventilation slightly during extreme cold peaks due to air mass retention. For very deep Midwest/Northern winters, some thick 3/4 inch + raw insulation pine hives often outperform lightweight cedar enclosures against shocking thermal change fluctuation; however, cedar will outlast the pine on pure structural integrity over 18+ years provided neither receives chemical contamination impacting beehives.

Look up specific agricultural extension recommendations published for your state or region; most official university guides standardize based on what provides the most robust external shell longevity within their typical climate data for the budget level common to that regional beginner cohort. (Searching:

“([Your State] Beekeeping Housing Requirements Extension”) often yields useful construction PDF sheets regarding standard framing/wood sourcing). Many extension guides generally list pine, fir, or poplar equally compatible provided moisture content management is paramount regardless of the wood, highlighting that preference toward Cedar or against it is largely anecdotal until discussing natural wood longevity specifically.

Key Builder Tip: Sealing Up Cracks is More Important Than Wood Choice

When setting up two core hive elements—the bottom board and the migratory or telescoping outer shell covers. These interfaces transmit major weather invasion risks. My cedar decision boils down to this: If you are paying for cedar boards, ensure that quality shows through precise joint connections rather than hoping the bees think it smells better. Gummy excess glue peeking out on the inside corner joints is still better construction than sloppy butt joints in every corner filled with raw empty air pockets that attract drafts of cold December outside air onto your brood stack. Bees defend seams, not plank choice. Your careful finishing reflects successful beekeeping management practices!

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ) for Beginner Apiarists

Do bees eat cedar wood to build their home?

No, bees do not “eat” sound structural wood to build their core colonies or nests. They choose cavities. Honeybees build internal structures from manufactured beeswax; no wood ingestion or structural integration happens by $textit{Apis mellifera}$. This idea often comes from observing carpenter bees, which drill boring tunnels into woods, but carpenter bees prefer softer, decaying wood, generally not commercial rough-grade construction cedar.

Is unfinished pine generally considered safe for beehives?

Yes, unfinished pine (raw pine lumber commonly bought at building suppliers if unmarked or untreated) is generally considered safe, effective, and the standard recommendation due to cost and broad availability. You must ensure it maintains thickness (at least 3/4-inch walls). Do not use pressure-treated pine as the chemical preservatives can significantly harm bees.

Should I paint or stain the outside of my cedar beehive?

It is absolutely best practice to leave the exterior of the cedar box bare, or wait until the box is fully assembled and the bees are present before applying anything. If sealing the exterior is mandatory to reach high durability expectations, wait until 3 or 4 curing cycles happen. Any paint or external sealant must be high-quality Exterior Latex or food/mineral oil finish only applied externally with drip runoff removal, never touching box gaps or hive faces internally in sections touching the frames or the bottom board.

What specific wood feature attracts bees the most in nature?

The chemical composition that truly attracts is found in nectar and pollen. For cavity selection, bees primarily value density (insulation capability), established internal volume (large, dark spaces over small ones), and strong, dry structural integrity capable of holding significant weight during major honeyflows in intense summer heat.

If I use cedar now, how do I future-proof it against issues?

Cedar inherently possesses good structural longevity due to rot resistance. Future proofing is managed via ventilation (prevent high internal moisture spikes), not wood choice differentiation, use thin metal shims or precise wood placement to control entrance sizing to regulate wasp airflow, and accept that rough cedar needs more external structural monitoring than smoothly sanded plywood construction might require.

Are wooden frames safe for their comb building, despite what I read about plastics?

Absolutely. Wooden frames are the industry main-stay used globally. Plastic frames sometimes allow burr/burr comb creation due to material flexibility; however, bees consistently choose carefully built-out structure first and foremost! Wooden frames set true with plastic foundation or wax starter strips work exceptionally for nearly all management styles.

Conclusion: Trusting Craftsmanship Over Anecdote

So, there you have it, friend! The big secret about cedar—it holds zero special magic (or mystical negativity) for constructing a quality beehive environment. We discovered that do bees like cedar wood** is driven less by scent and more by basic requirements: safety, stability, and excellent weatherproofing. Do not let misplaced excitement about its aromatic sales points or exaggerated structural repulsion myths dictate your budget or design choices at the expense of superior craftsmanship.

If you build true, clean, square joins reinforced correctly and prioritize incredible internal ventilation management, your bees will thrive whether their house boards ran you $5 or $50 across specialty cedar racks. Focus on learning safe structure utilization, understand humidity science applied to hive walls, and you will have robust, healthy colonies for years to come. Building this durability into your first few pieces sets a fine standard for every project you tackle thereafter. Welcome to the world of responsible home apiary support—you are already doing the hard part by seeking good, clear information! Keep testing, keep measuring twice, and always prioritize the health indicators when viewing movement within your cluster!