Are Oak Acorns Edible: Essential Survival Food

Yes, oak acorns are edible once properly prepared. While not a common food source today, their historical use and high nutritional value (carbohydrates, fats, proteins, and minerals) make them a valuable survival food. Proper processing is crucial to remove bitter tannins and make them safe and palatable for consumption.

Have you ever walked through an oak grove and wondered about those little nuts scattered on the ground? They’re acorns, and while they might look like simple tree litter, they hold a secret: many types of oak acorns are edible and can be a surprisingly nutritious food source in a pinch. For centuries, people relied on acorns, especially during lean times. If you’re curious about foraging or preparing for emergencies, understanding how to safely eat acorns is a fascinating skill. It might seem a bit daunting at first, but with a little knowledge and the right steps, you can unlock this natural pantry.

The Natural Bounty of Oak Acorns

Oak trees (genus Quercus) are abundant across many landscapes, and their acorns have been a staple food for humans and wildlife for millennia. Their nutritional profile is impressive, offering a good source of carbohydrates, healthy fats, protein, and essential minerals like potassium, calcium, and phosphorus. This makes them a hearty and energy-dense food, especially valuable in survival situations where access to conventional food sources is limited.

Why Are Acorns Not a Common Snack Today?

The main reason acorns aren’t a regular part of most diets is their high tannin content. Tannins are naturally occurring compounds that give acorns a bitter, astringent taste. High concentrations of tannins can also interfere with nutrient absorption and, in very large amounts, can cause digestive upset. Fortunately, these tannins can be leached out through various processing methods, making the acorns perfectly safe and even enjoyable to eat.

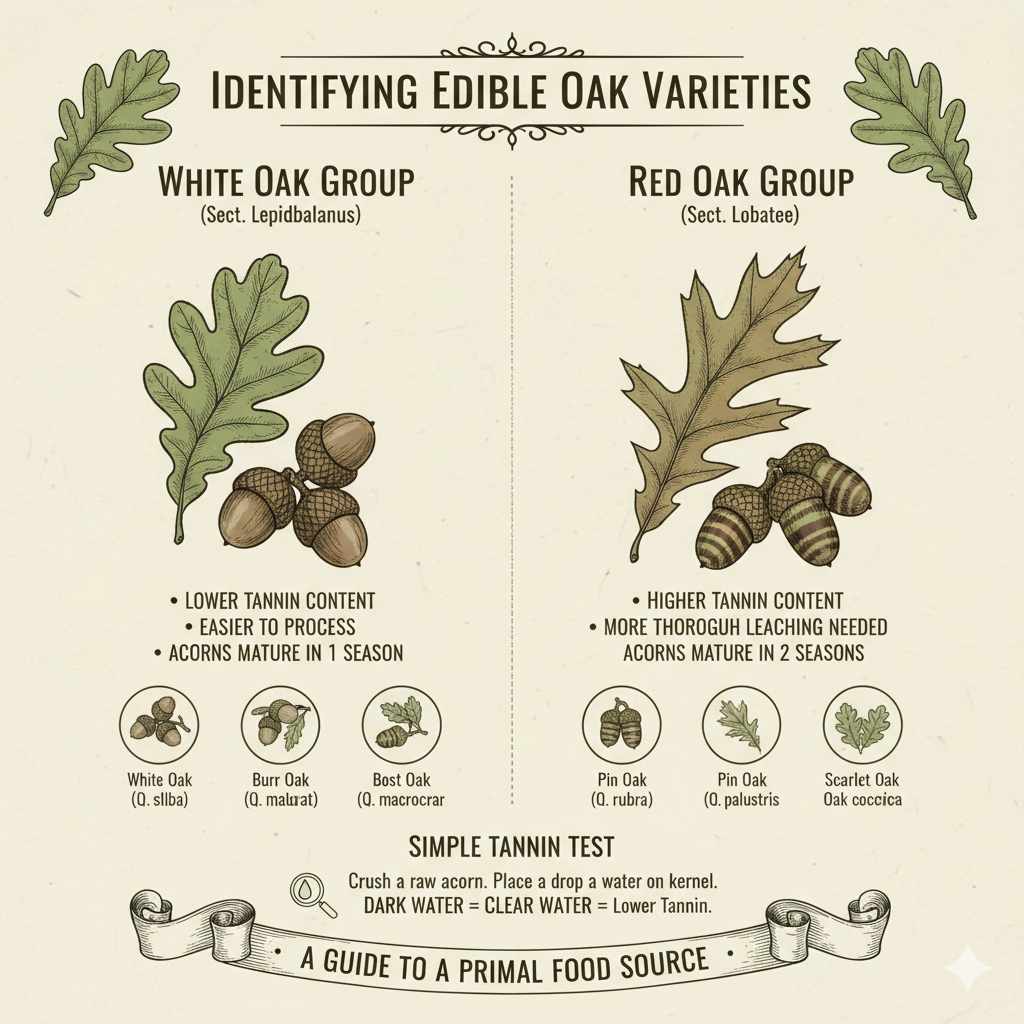

Identifying Edible Oak Varieties

While most oak acorns are technically edible after processing, some species are much better suited for consumption than others due to lower tannin levels.

Key characteristics to look for:

White Oak Group (Quercus section Lepidobalanus): These tend to have lower tannin content, making them easier to process. Examples include White Oak (Quercus alba), Burr Oak (Quercus macrocarpa), and Post Oak (Quercus stellata). Their acorns typically mature in a single season.

Red Oak Group (Quercus section Lobatae): These species generally have higher tannin content, requiring more thorough leaching. Examples include Red Oak (Quercus rubra), Pin Oak (Quercus palustris), and Scarlet Oak (Quercus coccinea). Their acorns often take two years to mature.

A simple test to gauge tannin levels: Crush a raw acorn and place a drop of water on the exposed kernel. If the water turns dark brown quickly, it has high tannins. If it stays relatively clear, tannins are lower.

Harvesting and Preparing Oak Acorns: A Step-by-Step Guide

Gathering acorns is a straightforward process, but preparing them requires a bit more care. The goal is always to remove the bitter tannins effectively.

Step 1: Harvesting Your Acorns

Timing: The best time to harvest acorns is in the fall, after they have fallen from the trees. Look for undamaged acorns that are free from wormholes or mold.

Selection: Prioritize acorns from the White Oak group if possible, as they require less processing. Collect a good variety, as some will inevitably be unusable.

What to Avoid: Discard any acorns that are moldy, punctured by insects, or have soft spots. These are likely spoiled and won’t be suitable for consumption.

Step 2: Shelling the Acorns

Once you’ve gathered your acorns, the next step is to remove the outer shell.

Methods: You can crack them open like nuts using a hammer or nutcracker. Alternatively, a quick way to loosen the shells is to boil the acorns in their shells for about 5-10 minutes. This softens the shell and hull, making them easier to peel.

Separating Kernel: After cracking or boiling, pry out the inner kernel. Discard the shells and the papery inner hull (cupule) if it remains attached.

Step 3: Leaching Tannins – The Crucial Step

This is where we get rid of the bitterness and make the acorns edible. There are several effective methods for leaching tannins.

Method 1: The Cold Water Leaching Method

This is the most common and often considered the most effective method for preserving nutrients.

1. Grind: Grind the shelled acorns into a coarse meal or flour. A coffee grinder, food processor, or even a mortar and pestle can be used.

2. Soak: Place the ground acorn meal in a large bowl or a clean cloth bag. Submerge this in a large pot or container of cold water.

3. Change Water: The water will turn yellow or brown as tannins leach out. You need to change this water frequently.

Frequency: Change the water every 2-3 hours for the first 12-24 hours.

Duration: Continue changing the water daily for several days (typically 3-7 days, depending on how bitter the meal is initially).

4. Taste Test: Periodically taste a small bit of the meal. When the bitterness is gone and the flavor is mild and slightly nutty, the leaching process is complete.

5. Drain: Once leached, drain the acorn meal thoroughly.

Method 2: The Hot Water (Boiling) Method

This method is faster but can result in some loss of nutrients and a slightly different texture. It’s particularly good for acorns with lower tannin levels.

1. Grind: Grind the shelled acorns into a coarse meal or flour.

2. Boil: Place the acorn meal in a pot and cover it with water. Bring to a boil.

3. Drain and Repeat: Drain the water immediately and refill with fresh water. Repeat this boiling and draining process several times.

Trials: You might need to boil and drain 5-10 times, or until the meal no longer tastes bitter.

4. Drain: Drain the meal thoroughly.

Method 3: The Rinsing Method (for specific acorn types)

Some acorns from the White Oak group have such low tannins that they can be prepared by simply rinsing the meal repeatedly with boiling water.

1. Grind: Grind the shelled acorns into a coarse meal.

2. Rinse: Place the meal in a fine-mesh sieve or cheesecloth. Pour boiling water over it, rinsing until the water runs clear and the meal no longer tastes bitter. This is the quickest method but is only suitable for the mildest acorns.

Step 4: Drying and Storing Your Acorn Meal

Once the tannins have been leached, you have edible acorn meal. You can use it immediately or dry it for storage.

Drying: Spread the leached acorn meal thinly on baking sheets.

Oven: Dry in an oven set to its lowest temperature (around 150°F or 65°C) with the door slightly ajar to allow moisture to escape. This can take several hours. Stir occasionally.

Dehydrator: Use a food dehydrator on a low setting.

Sun-Drying: In a dry, sunny climate, you can sun-dry the meal, though this takes longer and requires protection from insects and moisture.

Storage: Once completely dry and brittle, store the acorn meal in airtight containers in a cool, dark, dry place. It can also be ground into a finer flour once dried. Properly stored, it can last for several months.

Nutritional Value and Uses of Acorn Meal

Acorn meal is a versatile ingredient that can supplement your diet, especially in survival scenarios.

Nutritional Snapshot

| Nutrient | Approximate Amount (per 100g, cooked) |

| :————— | :———————————— |

| Calories | 350-450 kcal |

| Carbohydrates | 50-70g |

| Fat | 15-30g |

| Protein | 8-12g |

| Fiber | 10-20g |

| Minerals | Good source of Potassium, Calcium, Phosphorus, Magnesium |

Note: Nutritional values can vary significantly based on oak species and processing methods.

Culinary Applications

Once leached and dried, acorn meal can be used in a variety of dishes:

Bread and Pancakes: Substitute a portion of wheat flour in recipes for bread, muffins, or pancakes. It adds a dense texture and rich flavor.

Porridge: Cook acorn meal with water or milk to create a hearty porridge.

Thickener: Use it as a thickener for soups and stews.

Griddle Cakes: Mix with water to form a batter for griddle cakes, similar to traditional cornbread.

Pastries: Incorporate into cookie or pie crust recipes.

Safety and Considerations

While acorns are a valuable resource, it’s important to be aware of potential issues and practice safe foraging.

Tannin Toxicity

As discussed, tannins are the primary concern. Ingesting large amounts of unprocessed acorns can lead to:

Digestive Upset: Nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and abdominal cramps.

Nutrient Blockage: Tannins can bind to proteins and minerals, hindering their absorption.

Always leach acorns thoroughly until the bitterness is gone.

Identification is Key

Ensure you are harvesting from oak trees. Other nuts, like horse chestnuts, are toxic and should not be consumed. If you are unsure about tree identification, err on the side of caution. The U.S. Forest Service offers extensive resources for tree identification.

Processing Contamination

Ensure all containers, utensils, and water used during the leaching process are clean to prevent contamination.

Moderation

Even after proper preparation, acorn meal is dense. It’s best consumed in moderation, especially if you are not accustomed to it, to allow your digestive system to

adapt.

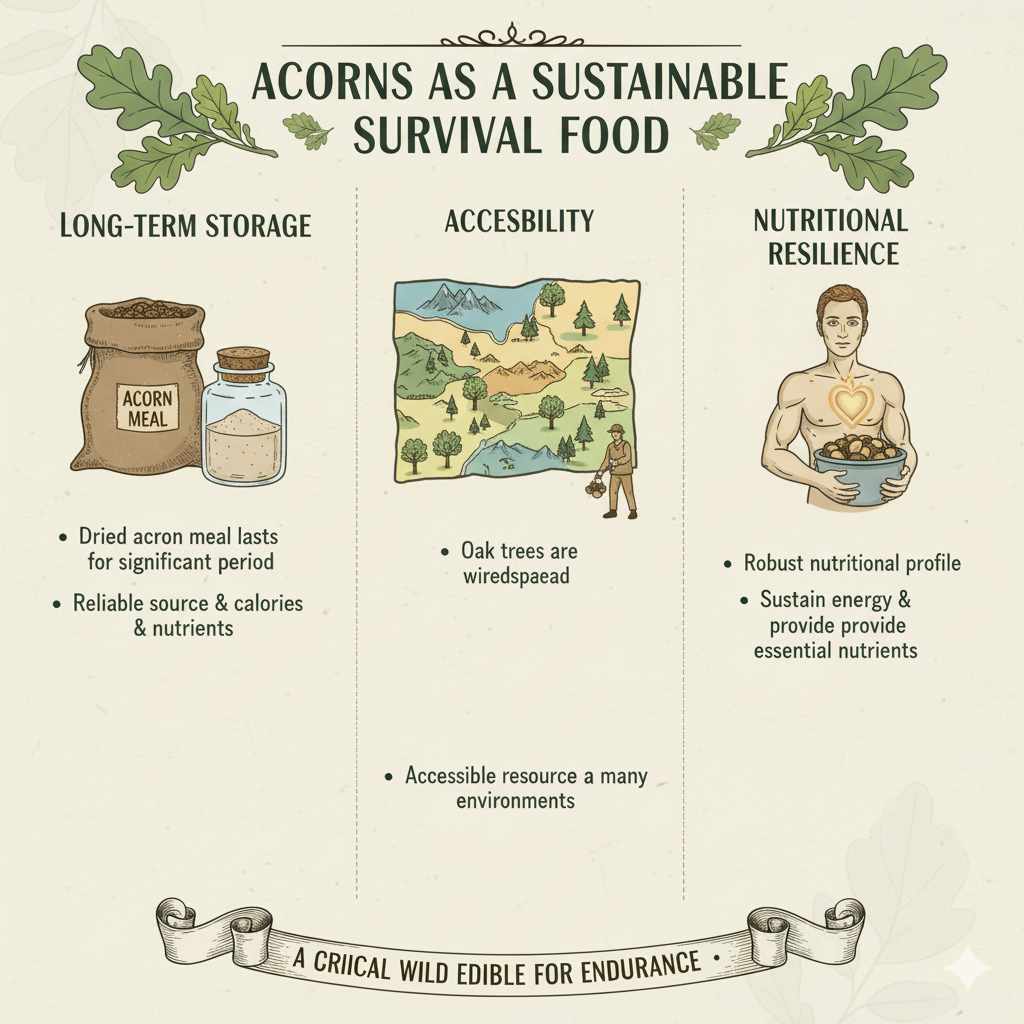

Acorns as a Sustainable Survival Food

In a genuine survival situation, knowledge of wild edibles like acorns can be the difference between enduring hardship and facing starvation.

Long-Term Storage

Dried acorn meal, properly stored, can last for a significant period, making it an excellent long-term survival food. This provides a reliable source of calories and nutrients when other options are unavailable.

Accessibility

Oak trees are widespread, making acorns a potentially accessible resource in many different environments. This widespread availability increases their value as a survival food for a broad range of people.

Nutritional Resilience

The robust nutritional profile of acorns means they can sustain energy levels and provide essential elements needed to survive challenging conditions. They are calorie-dense and nutrient-rich, offering a more complete nutritional package than many other wild edibles.

Frequently Asked Questions About Edible Acorns

Q1: Are all acorns edible?

A: While most oak acorns are technically edible after processing, some species have very low tannin levels making them easier to prepare. Others, particularly from the Red Oak group, have high tannin levels and require extensive processing. It’s always crucial to process acorns properly to remove bitter tannins.

Q2: What do unprocessed acorns taste like?

A: Unprocessed acorns are very bitter and astringent due to high tannin content. They can also cause digestive discomfort if consumed in significant quantities.

Q3: How long does it take to leach tannins from acorns?

A: The time required varies depending on the species of oak and the method used. Cold water leaching can take anywhere from 3 to 7 days, with the water being changed multiple times daily. Hot water leaching is faster but may require many boiling and draining cycles.

Q4: Can I eat acorns raw?

A: It is strongly advised not to eat acorns raw. They contain high levels of tannins that can cause digestive upset and interfere with nutrient absorption. Thorough processing is essential.

Q5: What is the best way to store acorn meal?

A: Once leached and thoroughly dried, acorn meal should be stored in airtight containers in a cool, dark, and dry place. It can last for several months when stored correctly.

Q6: Are there any poisonous trees that look like oak trees?

A: While no common trees produce nuts that are frequently mistaken for acorns and are poisonous enough to cause serious harm, it’s essential to be sure of your identification. Horse chestnut trees, for example, produce large nuts that are toxic and look somewhat like acorns but are from a different tree family. Always positively identify your tree as Quercus (oak) before harvesting acorns. Resources like those from Arbor Day Foundation can help.

Conclusion: A Skill Worth Mastering

Understanding whether oak acorns are edible and how to prepare them opens up a fascinating avenue for self-reliance and connection with nature. While not a daily staple for most, their potential as a nutritional powerhouse, especially in survival contexts, makes this ancient food source incredibly valuable. By following the steps for harvesting, shelling, and most importantly, leaching out those bitter tannins, you can transform a seemingly inedible nut into a versatile and nourishing ingredient. It’s a rewarding skill that harks back to our ancestors, reminding us of the abundance that nature can provide if we know where to look and how to prepare it. So next time you see acorns carpeting the ground beneath an oak, you’ll know they’re more than just fallen treasures – they’re a potential pantry waiting to be unlocked.