Can You Glue Sheetrock To Concrete? Essential Fixes

Bolded Quick Summary: Yes, you absolutely can glue sheetrock (drywall) directly to a clean, sound concrete wall using the right construction adhesive. This method, often called “direct application” or “drywall adhesive,” saves time by skipping the traditional framing process, but surface preparation is the most important step for a strong, lasting bond.

Are you staring at a bare concrete basement wall or a block foundation, wondering how to finish it without building out all those heavy wood studs? You’re not alone! Many DIYers want a fast, affordable way to get that smooth drywall finish right onto the concrete surface. People often worry if glue alone is strong enough. Well, I’m here to tell you that with the right supplies and a little know-how, gluing Sheetrock to concrete is a totally viable and time-saving fix.

You do not need to be a master carpenter to tackle this. We’re going to walk through every step needed to make sure your glued drywall stays put for years to come, focusing on prep, product choice, and perfect application. Let’s turn that rough concrete into a perfect wall surface!

The Beginner’s Guide to Gluing Sheetrock Directly to Concrete

When we talk about finishing concrete walls, the classic approach involves building a wooden frame, or “furring strip” system, first. This adds insulation space and gives you something secure to screw the drywall into. But for many homeowners, especially in basements or garages where space is precious, building that frame can be a hassle and eat up valuable square footage. That’s where the adhesive method—gluing drywall directly to the concrete—shines. It’s faster, often cheaper, and keeps your wall profile much thinner.

The success of this method rests entirely on two things: the condition of your concrete surface and the quality of the adhesive you choose. Think of the adhesive as your primary fastener. If the concrete is dusty, crumbling, or wet, the glue won’t grab, and your drywall will eventually fall off the wall. Safety first in all DIY jobs; before we grab the trowel, we must inspect and prepare the surface.

Assessing Your Concrete Surface: The Foundation of Success

Before any glue touches that concrete, we need to treat it like a quality piece of lumber—it has to be clean and ready to accept the finish. Concrete walls, especially in basements, present unique challenges like moisture, efflorescence (that white, chalky residue), and generally uneven surfaces.

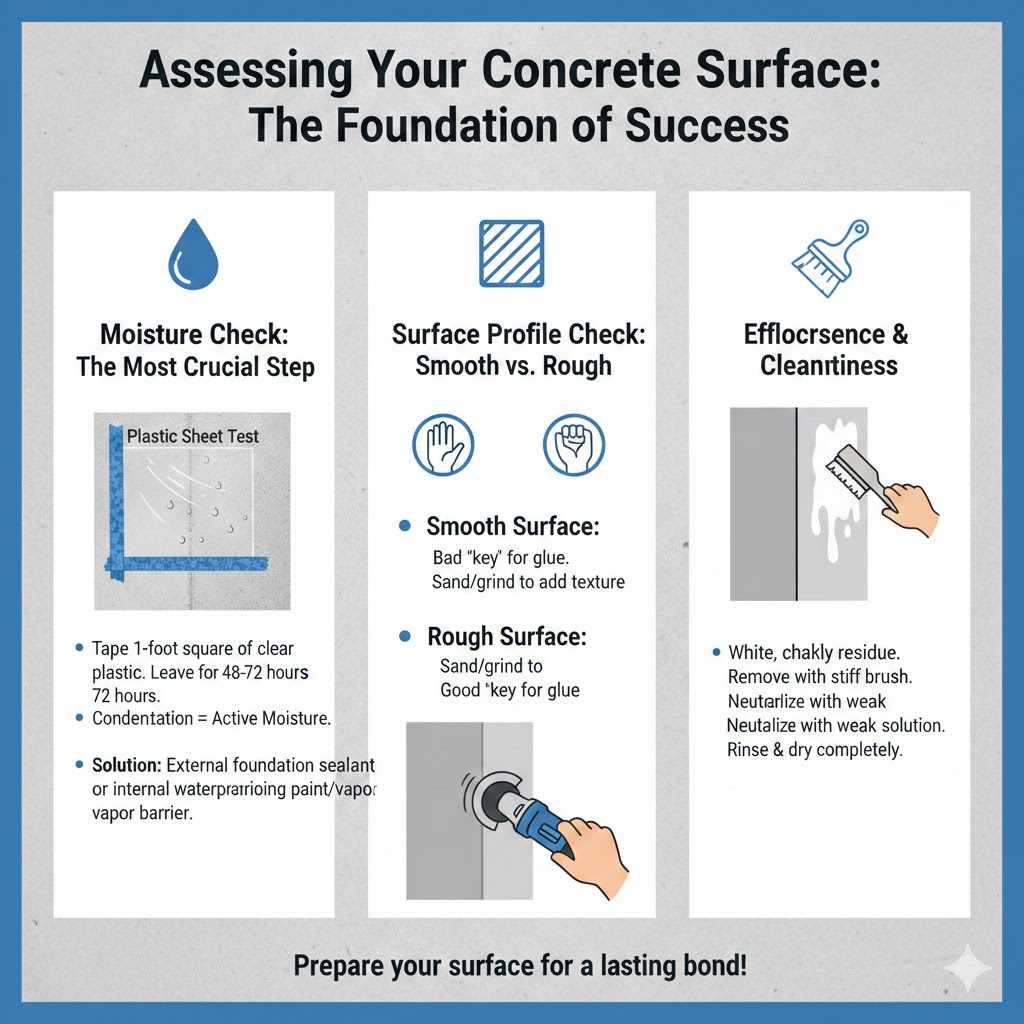

Moisture Check: The Most Crucial Step

Glue hates moisture, and moisture loves concrete, especially below grade. If your concrete wall is actively weeping water or showing signs of dampness, you cannot simply glue drywall to it. Water vapor transmission will cause mold, mildew, and the eventual failure of your adhesive bond.

Here’s a quick check you can perform:

- The Plastic Sheet Test: Tape a one-foot square of clear plastic sheeting (like a thick garbage bag) tightly to the concrete wall using construction tape. Leave it sealed for 48 to 72 hours. If you see condensation, moisture droplets, or dampness on the inside surface of the plastic, you have active moisture.

If you find moisture, you must address the source first. This might mean applying an external foundation sealant or, more commonly for DIYers, applying a quality waterproofing paint or specialized concrete vapor barrier product to the inside face of the wall before proceeding with any furring or drywall.

Surface Profile Check: Smooth vs. Rough

Your adhesive needs a good ‘key’—a surface it can physically grab onto. Smooth, sealed concrete is hard for glue to hold onto. Rough, unfinished concrete, cinder blocks, or even parged (smoothly covered) mortar joints offer a much better surface.

If the concrete is too smooth, or if you have existing paint that is shiny or peeling, you need to introduce texture:

- Sanding or Grinding: For shiny paint, a quick pass with a wire brush or a medium-grit sanding disc on an angle grinder can “dull” the surface enough for the glue to bite.

- Damp Wiping: If you have efflorescence (the white powder), this must go. Use a stiff brush to remove loose material. Then, you might use a weak solution of vinegar and water to neutralize any lingering alkalinity on the surface, followed by a thorough clean water rinse. Let it dry completely!

The goal is a surface that feels gritty and dry to the touch—no dust, no oil, no peeling paint.

Choosing the Right Adhesive: Glue is Not Just Glue

This is where many beginners make the mistake of reaching for the wrong bottle. Standard wood glue (PVA) will not work. Standard caulk won’t hold up. We need a heavy-duty, flexible, moisture-resistant adhesive designed specifically for construction bonding.

Adhesive Recommendations

When shopping, look for products explicitly labeled for direct application of drywall or paneling to concrete or masonry. These are usually solvent-based or advanced polymer formulas that offer excellent grab strength.

| Adhesive Type | Pros | Cons |

|---|---|---|

| Mastic/Heavy-Duty Construction Adhesive (e.g., PL Premium equivalent) | Extremely high strength, good gap-filling for slightly uneven surfaces. | Slower cure time, can be messy, requires adequate ventilation. |

| Specific Drywall-to-Masonry Adhesive | Optimized for the application, often thinner consistency for easier spreading. | May not bridge very large gaps between the drywall and concrete. |

| Foam-based Drywall Adhesive | Fastest setup time, excellent for leveling minor inconsistencies. | Requires specialized caulk gun/applicator, usually more expensive. |

My advice as a mentor? Go with a tried-and-true construction adhesive designed for paneling or framing. A good rule of thumb: If you think you need a box of nails or screws, buy an adhesive rated for high structural load bearing.

Why Specialized Adhesives Are Necessary

Standard interior glues are often water-based, meaning if the concrete has any residual moisture, the water in the glue stays trapped, leading to slow drying, poor curing, and eventual bond failure. The high-performance construction adhesives we use here contain polymers or solvents that allow them to bond tenaciously to porous, mineral-based substrates like concrete, and they are generally more resistant to minor shifts or vibrations.

Preparation for Application: Making the Job Easier

Even though we are skipping the full wood framing, there are a few preparatory steps that significantly boost the holding power and long-term integrity of your wall.

Creating a Minimal Furring/Shim Grid (Optional but Recommended)

For completely flat, level concrete, you can skip this. But let’s be honest—most older concrete foundation walls are wavy. If you glue a full sheet of drywall to a wavy wall, the whole sheet will bulge between the high spots, making taping and finishing impossible. The solution?

- Use Thin Furring Strips (or Wood Shims): Cut 1/4-inch or 1/2-inch plywood or reclaimed wood strips. Adhere these strips vertically to the concrete wall first, using the same construction adhesive.

- Leveling: Use a long level or a laser level to ensure these strips are perfectly plumb (vertically straight). The gaps between these strips will hold your drywall panels against a perfectly flat plane.

This hybrid method uses adhesive to attach the furring to the concrete, and then you’d normally screw the drywall to the furring. However, if you insist on only glue, you must ensure the adhesive layer perfectly fills the gaps created by the uneven concrete wall.

Applying Fastening Backup (Safety First!)

Even the best adhesive takes hours to fully cure. During this critical bonding time, gravity is working against you. For the first few sheets, especially near the top of the wall, you need temporary mechanical support.

What you need for support:

- Sturdy braces (T-braces used for framing work perfectly).

- Adjustable clamps or heavy-duty straps.

You will need to brace the bottom of the drywall sheet tight against the floor and the top tight against the ceiling joists until the glue sets—often 12 to 24 hours, depending on the product and temperature. Check your adhesive’s curing instructions religiously!

Step-by-Step Guide: Gluing Sheetrock to Concrete

This process assumes you have completed all necessary surface preparation, including moisture checks and cleaning.

Step 1: Cut Your Drywall Panels

Measure your wall height. Cut your 1/2-inch or 5/8-inch drywall panels to size. Remember that standard ceilings might have joists that drop down 16 inches from the ceiling plate. You should always leave a slight gap (about 1/4 inch) at the floor and ceiling for expansion and finishing mud.

Step 2: Apply the Adhesive Strategically

Do not coat the entire back of the sheet with glue—it will squeeze out everywhere and waste product. Adhesives work best when applied in beads or dollops that allow air movement and adequate bonding surface.

- Vertical Beads: Run two or three thick, continuous vertical beads down the back of the sheet. The beads should be roughly the size of a large sausage link.

- Adhesive Pattern: For extremely high strength, run one bead down the center, and then run a wavy bead around the perimeter, staying about an inch from the edge. This helps seal the edges when pressed.

- Waffle/Dab Pattern (If using Foam/Thicker Mastic): Apply large dabs of adhesive roughly every 12 to 16 inches in a staggered, grid-like pattern across the back. This is excellent for filling minor voids on rough concrete.

Pro Tip: If you are using rigid furring strips or blocking against the concrete, make sure you have glue on the back of the drywall where it will bridge over the empty space between the strips.

Step 3: Positioning and Pressing

Working quickly (some construction adhesives set very fast!), lift the panel into place. Start at the bottom corner that will serve as your baseline. Gently push the sheet onto the wall, using hand pressure across the entire surface.

- Don’t Over-Press: You want good contact, but you don’t want to squeeze all the adhesive out. If you see glue oozing out from the joints, ease up slightly. You want a glue layer thickness of about 1/8 to 1/4 inch after pressure is applied.

- Check for Flatness: Immediately check the panel with your long level or straightedge. If it isn’t flat, pull it off, scrape the glue off the panel (or scrape the wall), reapply the glue, and try again. Trying to “wiggle” it flat later won’t work once the glue starts setting.

Step 4: Secure with Bracing (The Temporary Hold)

Immediately after setting the panel plumb and level, brace it. Use your T-braces or prop boards. Secure the bottom edge tight to the floor (even though you left a gap, you are pressing against the concrete subfloor here) and brace the top edge securely against the ceiling joists above. The brace must apply consistent, upward pressure to counteract gravity while the adhesive cures.

Repeat this process for the adjacent panel, ensuring the edges butt tightly together for taping. Support both sheets independently or use adjacent panels to help support one another if they are completely secure.

Step 5: Curing and Finishing

Resist the temptation to tape the joints immediately. This is critical. Check the adhesive manufacturer’s cure time—this might range from 12 hours to a full 48 hours for high-strength structural bonds. Wait the full recommended time, especially in cooler, damper environments, before removing the bracing.

Once the bracing is removed and the wall feels rock solid, you can proceed with standard drywall taping, mudding, and finishing techniques. Because the sheet is glued edge-to-edge rather than screwed every 16 inches, you may notice slightly more flexing near the edges when mudding; take your time applying tape and embedding the first coat of mud.

Considerations for Different Concrete Types

Not all concrete surfaces are the same. Cinder blocks and poured concrete behave differently when glued.

Poured Concrete Walls

These tend to be smoother and might require aggressive wire brushing or grinding if sealed or painted. The key challenge here is preventing air gaps behind the panel if the pour wasn’t perfectly flat.

Cinder Block or CMU (Concrete Masonry Unit) Walls

These walls are incredibly porous and rough due to the deep mortar joints and the texture of the blocks themselves. This is often the best substrate for adhesive, as the rough surface offers fantastic grip.

- Gap Filling: You will need a thick adhesive pattern (or use foam adhesive) to bridge the deepest recessed areas of the block face.

- Pressure Points: Focus extra adhesive at the edges of the blocks to ensure the drywall isn’t just resting on the raised edges of the mortar joints.

For structural tips on handling concrete, reliable sources like the Building Science Corporation emphasize moisture control above all else when treating masonry walls.

Pros and Cons of the Adhesive Method

Like any building technique, gluing drywall has trade-offs. It’s important to weigh these before you commit to the entire wall.

Advantages (The Pros)

- Speed: It is significantly faster than framing, cutting studs, and positioning them.

- Space Saving: You gain back the 3.5 to 5.5 inches of space lost to traditional wall framing, which is vital in small rooms.

- Reduced Material Cost: You eliminate the cost of lumber (studs, plates, screws for the frame).

- Sound Dampening: A solid bond to concrete can sometimes offer better sound transfer resistance than a traditional wood frame assembly that acts like a drum.

Disadvantages (The Cons)

- Leveling Difficulty: Fixing a wobbly wall after the glue sets is nearly impossible without tearing it down. Any major unevenness must be addressed before installation.

- Permanence: If you need to access wiring or plumbing hidden in a false wall later, this method makes removal messy and destructive.

- Moisture Sensitivity: This method offers virtually zero ability to insulate the wall effectively without adding a secondary, non-adhesive layer, and if moisture issues arise, the problem is hidden behind the board.

- No Electrical Boxes: Mounting junction boxes or switch/outlet boxes is much trickier. You must block out the exact location and use specialized anchors that bite into the concrete around the drywall, or install shallow “old work” boxes spanning the gap if you used slight furring strips.

Addressing Electrical Boxes and Fasteners

One of the biggest hurdles when skipping wood framing is securing electrical boxes. Since you cannot simply screw a standard “new work” box into the stud behind the drywall, you need a specific strategy.

Strategy 1: Concrete Anchors (The Direct Mount)

If you use only adhesive, you must secure your electrical box directly to the concrete. This is achieved using special hardware.

- Mark the box location precisely on the concrete wall before hanging the drywall.

- After the drywall is up and the adhesive has set, use a small drill bit to punch through the drywall precisely where the box needs to sit.

- Using a masonry bit that matches the diameter of your concrete anchors (like Tapcons or specialized wedge anchors), drill pilot holes into the concrete through the pilot mark.

- Hold the electrical box up, line up the holes, and drive the concrete screws through the box body and into the anchor in the wall. You’ll need deep junction boxes if the drywall plus the adhesive is thicker than a standard “old work” box depth allows.

Strategy 2: Using Adhesive Tabs (For Non-Load Bearing Sections)

For light fixtures or conduit strapping, high-strength adhesive standoff brackets or magnetic bases (if you are adhering near a steel support) are fantastic secondary fasteners. Just ensure the bracket or standoff itself is rated for the load you intend to place on it. Don’t hang anything too heavy off an adhesive-only mounting point near the floor/ceiling joint until the adhesive has fully cured for several days.

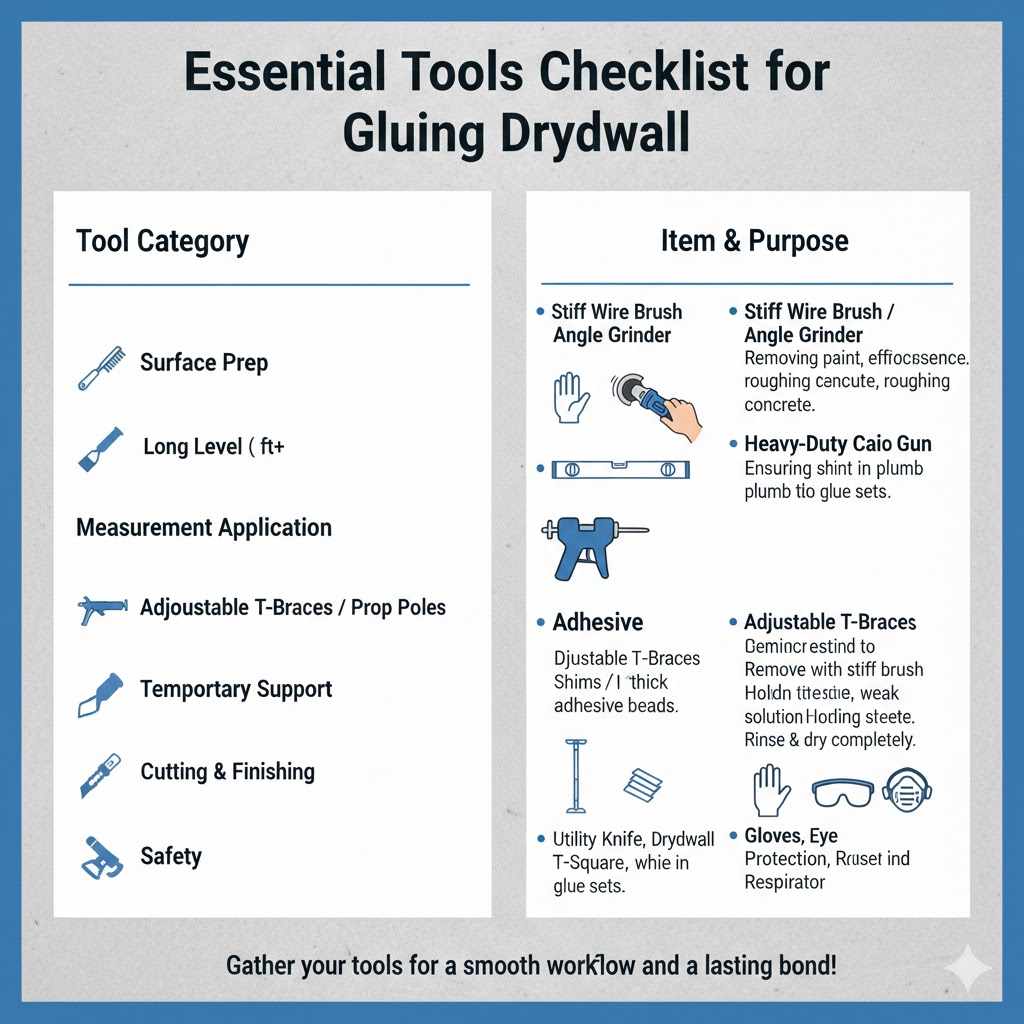

Essential Tools Checklist for Gluing Drywall

Gathering your tools beforehand ensures a smooth workflow. When dealing with construction adhesives, keeping things clean is half the battle.

| Tool Category | Item | Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Surface Prep | Stiff Wire Brush/Angle Grinder | Removing old paint, efflorescence, and roughing up concrete. |

| Measurement & Leveling | Long Level (4 ft or longer) | Ensuring sheets are plumb and perfectly flat across their height. |

| Adhesive Application | Heavy-Duty Caulk Gun | Dispensing thick construction adhesive beads reliably. |

| Temporary Support | Adjustable T-Braces or Shims/Prop Poles | Holding sheets firmly against the concrete while the glue sets. |

| Cutting & Finishing | Utility Knife, Drywall T-Square | Accurate scoring and cutting of the panels. |

| Safety | Gloves, Eye Protection, Respirator | Protecting skin from messy adhesive and lungs from dust/fumes. |

FAQs: Quick Answers for the Glued Drywall Beginner

Q1: Is gluing Sheetrock to concrete stronger than screwing it to studs?

No, generally not for seismic activity or direct impact, as screwing into solid wood studs offers maximum mechanical grip. However, high-quality adhesive offers superior vibration resistance and seals the entire surface, making it very strong for standard, finished interior walls.

Q2: What is the minimum thickness of drywall recommended for this method?

We strongly recommend 1/2-inch drywall for better stiffness. If your concrete surface is very uneven, 5/8-inch Type X is preferable because its rigidity resists bowing between adhesive points better than the thinner 1/2-inch board.

Q3: Can I use standard drywall mud to finish joints glued directly to concrete?

Yes, once the construction adhesive has fully cured (do not rush this!), you finish the joints exactly as you would any standard drywall installation using all-purpose or topping compound and paper or fiberglass tape.

Q4: Does this method work well for basement walls prone to sweating?

Absolutely not. If you have surface condensation (“sweating”) or moisture vapor transmission, the moisture will get trapped between the glue and the concrete, leading to mold or adhesive failure within a year or two. Always install a vapor barrier or rigid foam insulation board first, then glue drywall to the foam.

Q5: How wide should the beads of adhesive be on the back of the drywall?

For most standard construction adhesives, aim for beads about 1/2 to 3/4 of an inch thick (think thick sausage link). They should run vertically along the sheet, spaced about 12 inches apart for maximum contact across the entire panel area.

Q6: What happens if I pull off a piece of drywall glued this way later?

If the bond was successful, you will destroy the face paper of the drywall and likely tear chips out of the concrete surface itself. The glue forms a mechanical bond that is stronger than the material it’s adhered to. This confirms that surface prep must be excellent, as repairs will be difficult.

Q7: Do I need to anchor the bottom edge of the glued sheet?

While you don’t screw it in, you must temporarily anchor it using bracing (as mentioned above) because the initial grab of the glue is not enough to hold the heavy sheet vertically against gravity. You should leave a small 1/4-inch gap at the floor line that will be covered by the baseboard trim.

Final Thoughts on Craftsmanship and Adhesion

Mastering the art of gluing Sheetrock to concrete is a fantastic trick to have in your DIY toolbox. It allows you to accomplish major renovations quickly without dedicating entire weekends to building complex wood frames. Remember, this is an exercise in preparation and patience. The physical act of slapping the glue on takes five minutes; ensuring the concrete is perfectly clean, dry, and ready to hold that weight takes an hour or more. Do the prep work correctly, choose a heavyweight adhesive, and use temporary bracing religiously.

When you finally remove those braces after the cure time and give the wall a solid thump—hearing that reassuring, dense thud—you’ll know you’ve achieved a lasting, durable finish. You have effectively bypassed an entire framing step using modern chemistry. That’s smart building! Keep practicing these direct-attachment techniques, and you’ll find that every wall, whether wood or masonry, becomes an achievable surface for a beginner homeowner like yourself.